Pat Connors – Gaeltach Man of the Sea

Pat had a lovely way of rustling up a tasty snack after a night’s fishing. He’d shake up the turf fire in the kitchen, throwing on another sod if necessary. Then he’d place three or four eggs into a kettle of water for the tea and sit back warming his stocking’d feet to the open fire as the kettle boiled and the eggs cooked. Thick buttered slices of homemade brown bread would be spread with the soft-boiled eggs and the whole lot washed down with tea so strong a mouse could trot on it. As Rachel Allen would say: “Mmmm. Delicious!”

Like many of his neighbours on the Dingle peninsula, Pat Connors had been forced to emigrate to America as a young man and had spent many years labouring on the building sites in Chicago & New York before eventually returning home to Baile Dhá on the shores of Smerwick Bay in Corca Dhuibhne, West Kerry. He divided his time between running his small farm, rearing a family and, his great love, hunting salmon in the waters lapping the Blasket Islands.

Pat Connors had spent many years labouring on the building sites in Chicago & New York

To supplement their family income, Pat and his lovely, gentle wife, Peig, took in Irish language students during the summer and this is how I first met them in the early 1970s, bringing students from my school in Cork to the West Kerry Gaeltach for the month of June. Their house became a home away from home and Pat & Peig became lifelong friends. He divided his time between running his small farm, rearing a family and, his great love, testing his wits against the Atlantic Ocean in a small currach – or naomhóg – hunting salmon in the waters lapping the Blasket Islands.

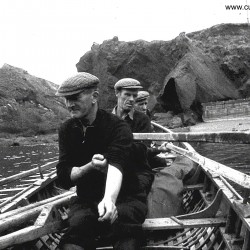

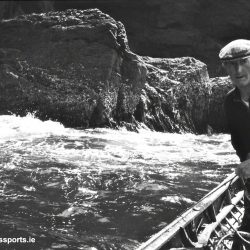

I was fascinated by the naomhóg and couldn’t understand how such a flimsy craft could survive on the mighty Atlantic. It consisted simply of lengths of tarred canvas stretched tight over a latticework of light timber rib-frames surmounted by a gunwale. It had no keel and the rowers – usually three – used long, narrow oars with no ‘blade’ at all and it was a wonder to me how such a slender vessel could ride out large ocean waves with three men and, maybe, a sheep or two on board.

I ventured forth with Pat and two of his neighbours, Bill Ó Cathaláin and Nick Ruiséal, one morning in June 1972. We were to go fishing for salmon using a drift net, which was the way in West Kerry. A drift net was a narrow net, many hundreds of yards long and made of fine filament about ten feet deep. It hung in the water in a long line, supported on one side on the surface by pieces of cork. The salmon was a surface swimming fish and particularly vulnerable to this method of fishing. The net would be left there floating unattended for some hours and was lethal should a fish swimming anywhere near the surface strike it head on. Its gills would be caught in the net, it couldn’t back out and the fish, strangely enough, would drown.

We were to go fishing for salmon using a drift net, which was the way in West Kerry

I sat, wedged in the brow of the boat with my camera, as we pushed off from Dunín Pier early one morning and the first thing I noticed was how easily she rose to every swell and how responsive she was to every pull of the spindly oars as we skimmed across the water. Pat stood amidships leaving out the net as we went. Within an hour we were back again at Dunín with the net laid and all we had to do now was wait until evening before venturing out again to haul the net and, hopefully, reap a bountiful harvest.

The men sat on the headland overlooking the bay smoking their pipes as they kept watch on their net far out from the shore. They talked and ‘their talk was a theme of Kings.’ The price of sheep, Kerry football, a local death in the parish. Eventually one man jumped to his feet and cried out excitedly, “Táid ann! Táid ann!” (They’re there! They’re there!).

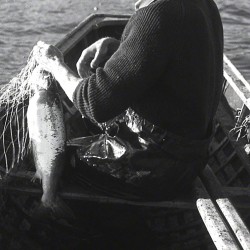

I could see nothing only the sun glancing off the swell but the men knew what they were about and in a few short hours we were back on the swell and heading out the bay to where the net hung innocently in the water. Sure enough, as the net was hauled back on board we could see our silver harvest glistening in the water. Soon and we were heading for shore with a dozen or more fine fresh salmon lying at our feet at the bottom of the boat.

And afterwards, the brown bread, the boiled eggs and the tea.